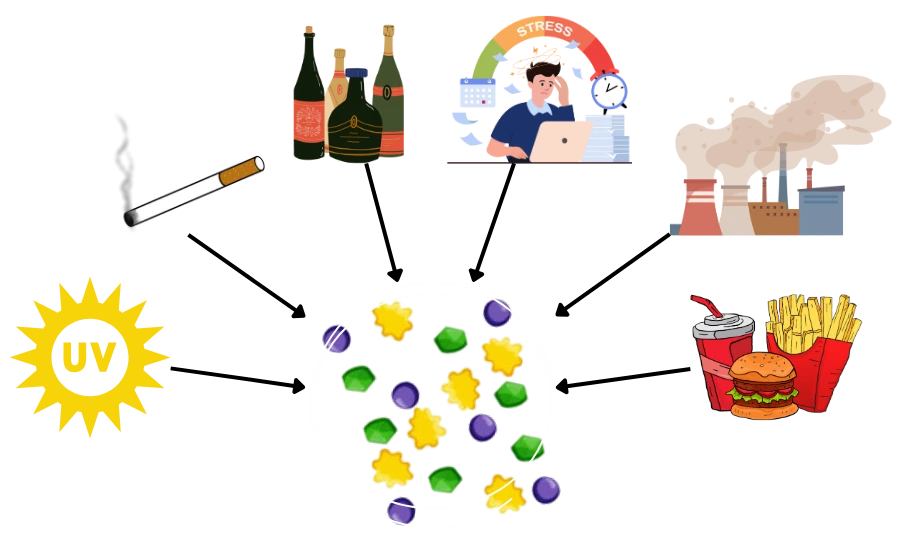

The biochemistry of free radicals and how they cause damage

Free radicals are atoms or molecules that have one or more unpaired electrons. These unpaired electrons are highly reactive because atoms

and molecules tend to seek a stable electron configuration. Free radicals can be produced during chemical reactions—for example, as a result

of oxygen metabolism or exposure to radiation. In biological systems, they can cause damage by reacting with other molecules and attempting

to steal electrons from them, creating instability and harm within cells. Free radicals are continuously generated in our bodies, and under

normal conditions our antioxidant systems keep them under control. However, external factors such as cigarette smoke, environmental

pollutants, and UV radiation can increase free radical production and overwhelm the body’s antioxidant capacity. Free-radical damage can

include DNA strand breaks, structural changes in proteins, and lipid oxidation—processes that contribute to cellular aging and the

development of various diseases.

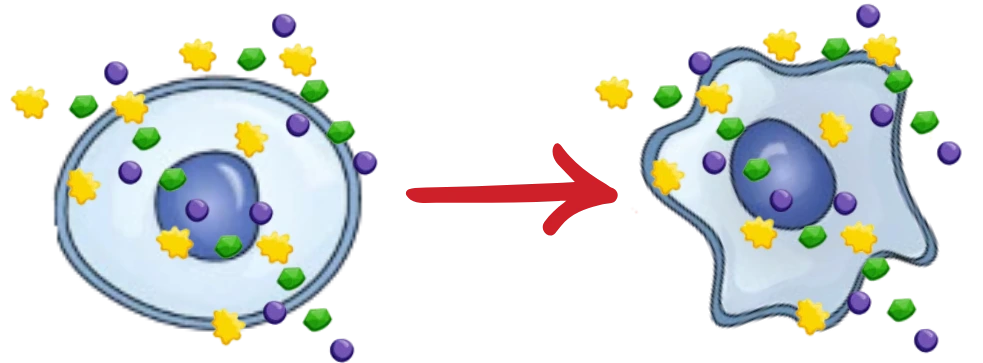

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress and its harmful effects can impact cells and the entire body. Oxidative stress can cause damage at the cellular level as

well as across organ systems:

Key cellular-level effects of oxidative stress

- Impaired mitochondrial function: mitochondria—the energy-producing centers of cells—are highly sensitive to oxidative

stress. Mitochondrial dysfunction can disrupt energy production, which in turn affects virtually every other cellular function.

- DNA damage: oxidative-stress-induced DNA damage can have serious consequences, including genetic mutations, cancer

development, and accelerated aging processes.

- Protein and lipid damage: damage to proteins and lipids in cell membranes and within cells disrupts normal cellular

function and can lead to dysfunction and cell death.

Body-wide effects of oxidative stress - Nervous system: the brain and nervous system are particularly sensitive to oxidative stress, which may contribute to

the development of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

- Cardiovascular system: oxidative stress may play a role in cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and heart

attack.

- Immune system: excessive oxidative stress can weaken the immune system, reducing the body’s ability to defend against

infections and disease.

- Skin: the skin, as the body’s external protective layer, is also sensitive to oxidative stress, which may promote aging processes

and contribute to skin conditions.

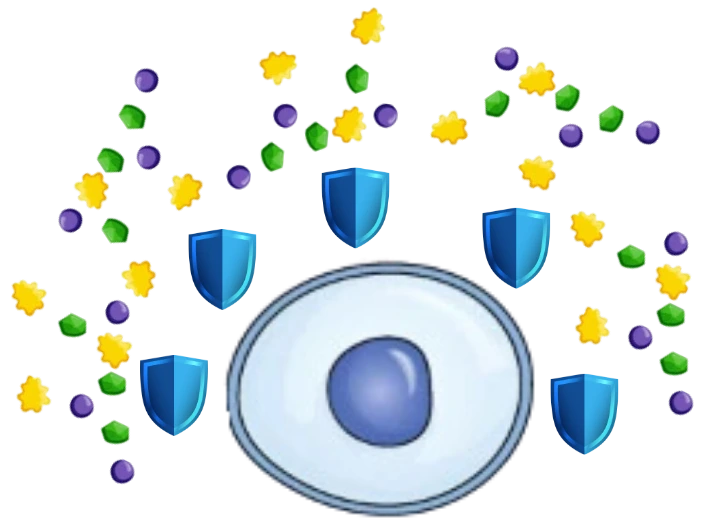

Your body’s internal defense system

The body has many defense mechanisms against oxidative stress. Internal antioxidant systems include various antioxidant enzymes and

molecules that neutralize free radicals and reduce oxidative damage. These internal systems are crucial for protecting cells and play a role

in aging and in supporting the prevention of various diseases.

Glutathione

Glutathione is central to combating oxidative stress and cellular aging. It is a key internally produced antioxidant that plays

a vital role in detoxifying harmful compounds and maintaining cellular redox balance. Glutathione directly neutralizes reactive oxygen species

(ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), helps repair oxidative damage, and supports the regeneration of other antioxidants such as vitamins

C and E.

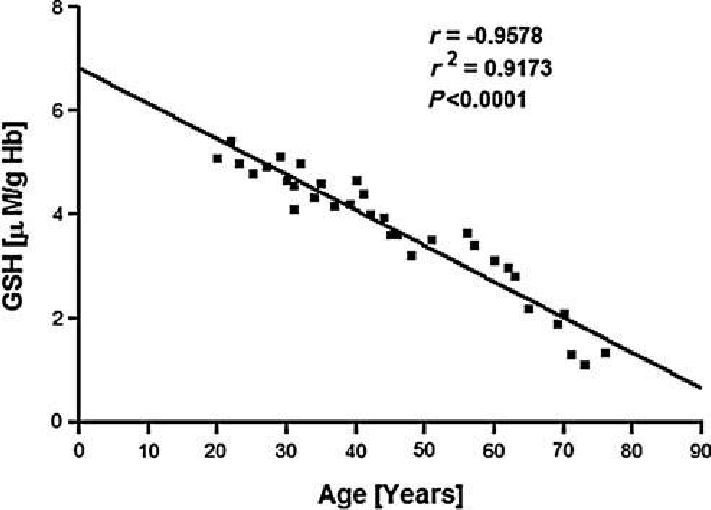

How glutathione levels change

Glutathione production declines with age.

This decline is associated with weaker antioxidant defense in cells, which increases oxidative damage and contributes to aging processes. The decrease in glutathione levels may be driven by reduced activity of glutathione-synthesizing enzymes and by reduced availability of

its precursors (cysteine and glycine). Lower glutathione not only accelerates aging processes but also increases the risk of various health

problems. When glutathione levels are low, cells are less able to defend against oxidative-stress-related damage, which may contribute to

chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. In addition, glutathione deficiency has been associated with

a higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s (Ballatori, et al., 2009).

Limitations of direct glutathione supplementation

Although direct glutathione supplementation may seem like the most obvious solution, it is unfortunately not very effective. As a dietary

supplement, glutathione is not absorbed efficiently and does not readily cross cell membranes, so it does not reliably reach the cells where

it is most needed. For this reason, direct glutathione supplementation has limited effectiveness in increasing the body’s antioxidant

defenses (Richie et al., 2015).

GlyNAC as a way to support glutathione production

Fortunately, glutathione levels can be effectively increased by supplementing its precursors.

The critical building blocks of glutathione are cysteine and glycine; the third component, glutamine, is generally produced by the body in sufficient

amounts.

GlyNAC—containing glycine and N-acetylcysteine (NAC)—is a specific combination that, according to recent research, can effectively increase glutathione

levels (Sekhar et al., 2011).

NAC provides cysteine, which may increase antioxidant capacity and reduce oxidative stress.

Glycine has anti-inflammatory properties and helps protect cells from various stressors.

Thanks to the synergy of GlyNAC, glutathione production can be significantly increased, which may improve mitochondrial function and slow cellular

aging.

GlyNAC not only plays a role in combating oxidative stress, but also supports mitochondrial health and may indirectly help reduce inflammation.

This provides a comprehensive, research-based approach to key aspects of cellular aging.

References

-

Yang CS, Chou ST, Liu L, Tsai PJ, Kuo JS. Effect of ageing on human plasma glutathione concentrations as determined by high-performance

liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detection. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1995 Dec 1;674(1):23-30. doi:

10.1016/0378-4347(95)00287-8. PMID: 8749248.

-

Kumar, Prabhanshu & Maurya, Pawan. (2013). l-Cysteine Efflux in Erythrocytes As A Function of Human Age: Correlation with Reduced

Glutathione and Total Anti-Oxidant Potential. Rejuvenation research. 16. 10.1089/rej.2012.1394.

-

Ballatori N, Krance SM, Notenboom S, Shi S, Tieu K, Hammond CL. Glutathione dysregulation and the etiology and progression of human

diseases. Biol Chem. 2009 Mar;390(3):191-214. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.033. PMID: 19166318; PMCID: PMC2756154.

-

Richie JP Jr, Nichenametla S, Neidig W, Calcagnotto A, Haley JS, Schell TD, Muscat JE. Randomized controlled trial of oral glutathione

supplementation on body stores of glutathione. Eur J Nutr. 2015 Mar;54(2):251-63. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0706-z. Epub 2014 May 5. PMID:

24791752.

-

Kumar P, Liu C, Hsu JW, Chacko S, Minard C, Jahoor F, Sekhar RV. Glycine and N-acetylcysteine (GlyNAC) supplementation in older adults

improves glutathione deficiency, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction,

genotoxicity, muscle strength, and cognition: Results of a pilot clinical trial. Clin Transl Med. 2021 Mar;11(3):e372. doi:

10.1002/ctm2.372. PMID: 33783984; PMCID: PMC8002905.

-

Kumar P, Liu C, Suliburk J, Hsu JW, Muthupillai R, Jahoor F, Minard CG, Taffet GE, Sekhar RV. Supplementing Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine

(GlyNAC) in Older Adults Improves Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Inflammation, Physical Function,

and Aging Hallmarks: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023 Jan 26;78(1):75-89. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glac135.

PMID: 35975308; PMCID: PMC9879756.

-

Sekhar RV. GlyNAC (Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine) Supplementation Improves Impaired Mitochondrial Fuel Oxidation and Lowers Insulin

Resistance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Results of a Pilot Study. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Jan 13;11(1):154. doi:

10.3390/antiox11010154. PMID: 35052658; PMCID: PMC8773349.

-

Sekhar RV, Patel SG, Guthikonda AP, Reid M, Balasubramanyam A, Taffet GE, Jahoor F. Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies

oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Sep;94(3):847-53.

doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.003483. Epub 2011 Jul 27. PMID: 21795440; PMCID: PMC3155927.